Michael S. Martin, Executive Director of the Rowland Foundation

[adapted from an August 1, 2025 letter to Rowland Fellows]

Sometimes it feels like nothing ever changes in schools. Even as the news cycle spins faster and faster, there’s a weird inertia in education. Looking back, I was a young teacher before schools were connected to the Internet, before email, before 1:1 programs, before social media and “smart phones”, before Zoom, and, most obviously, before Chat GPT. Without a doubt, each of these waves of disruptive new technology wreaked major changes on our brains, relationships, pastimes, sleep, and self-concept… and yet, none of them really transformed schools as promised.

These new products have altered how students experience school, but not what some researchers call the grammar of schooling. In short, these are the “baked-in” structures of school that go largely unexamined because they’ve been in place for generations. Tyack & Cuban give the examples of dividing the curriculum into conventional subject areas; grouping students by age; classrooms of about 25 students with a single teacher As part of his case for a shift to deeper learning, Jay Mehta illustrates the grammar of schooling here. You can also explore this idea further in Deeper Learning for Democracy: Realizing a New Vision for Public Education in Vermont (2024), a white paper written by Rowland Fellows Andrew Jones, Jess DeCarolis, Gabriel Hamilton & Michael Ruppel.

“…these are the baked-in structures of school that go unexamined…”

To further illustrate this idea, here’s another way to think about the grammar of schooling. For most students, school still consists of going to a specific set of rooms in a single building where a teacher trained in a specific content area delivers information from that domain, shows you how to develop some related skills, and rates your success (see Freire’s Banking Model of Education). Most students and teachers are required to stay in that building from roughly 8:00 am to 3:00 pm. In order to control large numbers of people in the same building, freedom of movement and speech are controlled and curtailed (see William Glasser or Peter Gray). The physical spaces in schools are mostly noisy and uncomfortable (lots of cinderblock, linoleum, laminate wood, metal, and hard plastic), and the long straight halls, stark commons areas, and double doors can seem like a softer version of prison, especially since so many U.S. schools have “hardened” their facilities in the wake of school shootings.

However, the grammar of schooling is not just the physical environment and daily schedule, but also the beliefs and practices that dominate schools. For example, schools put much more energy into ranking and sorting students than developing each student’s unique gifts and aspirations. Even when schools don’t use explicit tracking, students are often still sorted by various labels which shape their daily school experience: Honors Students, Multilingual Learners, AP kids, At-Risk Learners, Special Ed students, Tier 2 students, “high flyers”, “disengaged learners”, “oppositional students”… This extensive use of labeling young humans shapes both teacher and student expectations in powerful ways (see Shalaby).

“In a different universe, our schools could focus more on learning than labeling.”

And whether it’s a 100-point scale or a 4-point scale, we still tend to rate students comparatively, as on a bell curve, instead of a criterion-based system where the goal is for everyone to meet the standard. Of course, all this labeling and ranking goes into the mother of averages, the Class Rank, where all students of a particular grade are listed top-to-bottom by Grade Point Average. My point here is that all this labeling, ranking, and sorting requires energy and resources that could have gone into teaching and learning. Over-evaluation actually leads to less teaching and high-quality feedback. Guskey observed that our school structures are mostly designed to select talent, not develop talent. In a different universe, our schools could focus more on learning than labeling.

What’s more, the cultural codes of school were defined by middle-class white people for middle-class white people. In this way, schools confirm, reinforce, and reproduce class differences, while posing as neutral arbiters of our meritocracy (see Bourdieu). Our students see through this. They know that the Game of School is not played on a level playing field.

Perhaps the most unexamined aspect of the grammar of schooling in the U.S. is our supposed support for the democratic mission of school, even though we don’t teach or practice democracy in the way we do school (see bell hooks or Dewey). This is more than a hole in our curriculum. This disconnect between what we say and what we do undermines our credibility in the eyes of our students.

Even if they don’t figure on Mehta’s list, all of the above could be considered aspects of The Grammar of Schooling, in effect the hidden operating system of how we do school.

“…effects that ripple throughout the system and shift the culture and climate of schools in ways our young people can feel.”

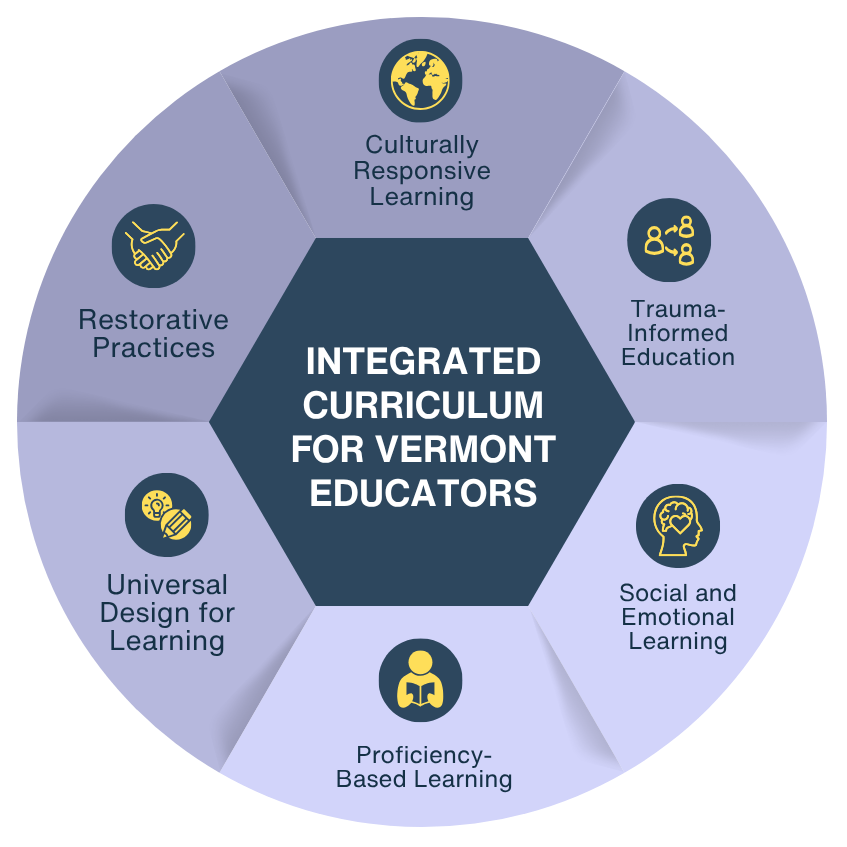

These structures and practices largely define school, regardless of the latest technology that we bring into the classroom. In fact, it’s astounding how impervious to technological innovation the grammar of school has proven, like an embedded code we have forgotten how to reprogram. Fortunately, there are other kinds of innovation that can make a real difference. I think right away of Rowland Fellowship work, focused on things like community-based learning, nature-based education, student voice and choice, authentic assessment practices, and restorative justice. All of these approaches can be game-changers. Particularly when implemented at scale, rather than as small alternative programs, they can have effects that ripple throughout the system and shift the culture and climate of schools in ways our young people can feel.

As Artificial Intelligence (AI) and other technology takes up more and more space in our lives, we need to keep nurturing human intelligence. We need healthy and vibrant in-person learning communities, where technology is working for us, not the other way around. So let’s keep innovating more human approaches to school — and keep questioning outdated grammars of school along the way.