Emily Gilmore Hurwitz, Senior Associate, Great Schools Partnership, Inc & 2017 Rowland Fellow

Almost 10 years ago, I crafted my original Rowland Fellowship proposal dreaming of what school could look and feel like by actualizing the vision of Vermont’s Act 77. That legislation was intended to move high school education in our state away from a one-size-fits-all model toward more personalized learning. The objective of my Fellowship work, I wrote, would be “to explore the integration of growth mindsets, personalized learning plans, and proficiency-based graduation requirements” as we rethought graduation requirements at South Burlington High School, where I was teaching at the time.

As I explored the intersections of proficiency-based learning, growth mindsets, and personalized learning plans, I came to understand that conversations around student outcomes were most connected to racism and the intersectionality of historically marginalized identities. Indeed, the greatest change in my own thinking around Act 77 has been a much deeper and robust understanding of how educational inequities are at the root of our systems’ shortcomings.

Through my Rowland Fellowship work with students and colleagues, I saw that schools would introduce new initiatives and focus areas in hopes of ensuring just outcomes on the one hand, while failing to address opportunity gaps among students on the other. Social-Emotional Learning (SEL), Universal Design for Learning (UDL), Trauma-Informed Practices (TIP), differentiation, advisory, performance tasks — the list goes on. As educators of color have been researching and sharing for decades, none of these initiatives can have the intended impact on all students unless they also challenge imbalances of power and privilege in predominantly-white educational spaces.

The student committee created through my Fellowship evolved over the years to focus on issues I hadn’t originally imagined. We looked for ways to evaluate curriculum to find whose stories were being told and how. We explored UDL and thought deeply about which design considerations could be most useful in the classroom and when. We researched the history of race and racism and questioned SEL and TIPs that omitted the impacts of racism, ableism, sexism, and so on. We discussed proficiency-based learning as a tool to disrupt eugenic thinking and its influence on our modern grading system, so focused on ranking and sorting.

“…working to actualize new standards takes time and requires educators to take risks and make mistakes.”

I came to believe that educational reforms like those proposed in Act 77 can only be powerful when they are designed with an anti-racist, anti-bias focus. I now work at Great Schools Partnership (GSP), a non-profit focused on redesigning public education and improving learning for all students. At GSP we define educational equity as “ensuring just outcomes, raising marginalized voices, and challenging the imbalances of power and privilege.”

Meanwhile, in the intervening years, the state of Vermont has adopted new Education Quality Standards, reimagined by the Act 1 Working Group, which was organized around the value of raising marginalized voices. These new standards name so many of the lessons my students and I learned — among them, that working to actualize new standards takes time and requires educators to take risks and make mistakes.

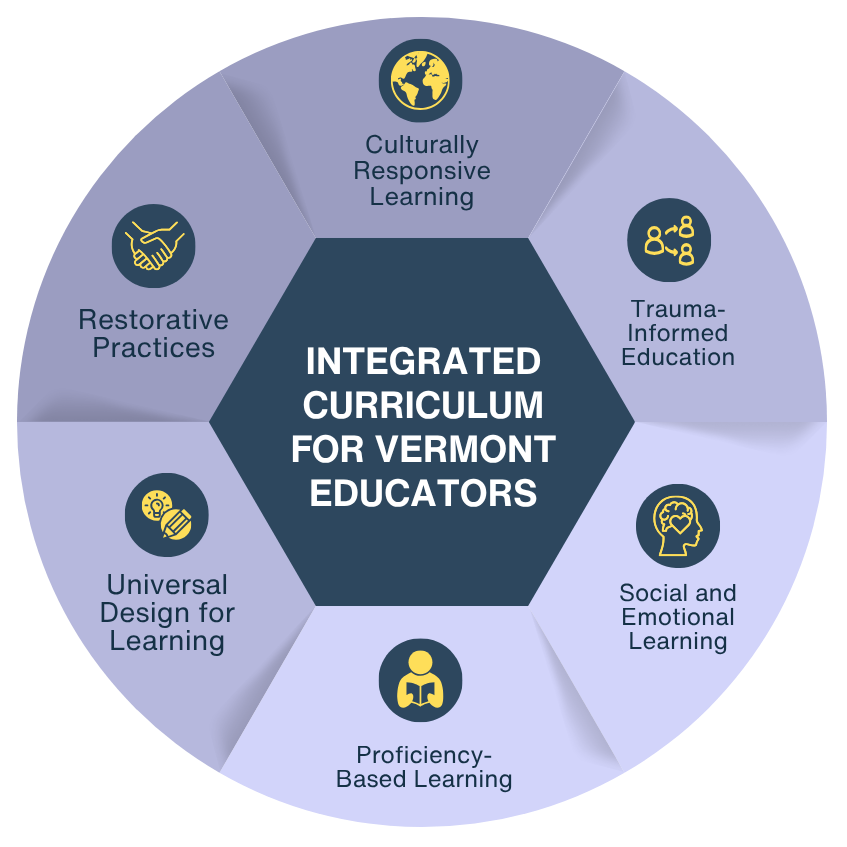

Fortunately, the Rowland Foundation is committed to just this kind of educational innovation. During the past year, through the newly-created New Teacher Fund, The Rowland Foundation supported GSP in developing the Integrated Curriculum for Vermont Educators (ICVE). The Integrated Curriculum is a tool for educators in Vermont and beyond to create meaningful, accessible, and inclusive learning experiences. It takes the lofty goals of the new EQS — to afford all Vermont students access to “educational opportunities that are substantially equal in quality and are equitable, anti-racist, culturally responsive, anti-discriminatory, and inclusive” — and gives educators concrete approaches to try with students. It demonstrates how Vermont’s IRIS Ethnic Studies Standards can be used to enhance unit design, and how educators are already imagining how this can happen in their own classrooms.

Since I first started researching what student-centered, personalized, proficiency-based learning could be in a comprehensive high school, the discourse around what schooling should look like in Vermont has changed dramatically. At the same time, the challenges our schools face today are eerily similar to those of a decade ago. In some ways, working on the ICVE has brought my Rowland Fellowship work full-circle. As the ICVE shows, when we focus on educational equity, we can implement other reforms with greater success and put truly just outcomes within reach.